Out there

Friends

Commentary

Web design

Graphics

Computers

Painting

Photography

Klaus Nordby's militantly dull homepage

www.klausnordby.com/ego/bg-oct29.html

06-Apr-07

23:48

Bouguereau painting forgery blog

October 29, 2006: Brief explanation of transparent vs. opaque paint

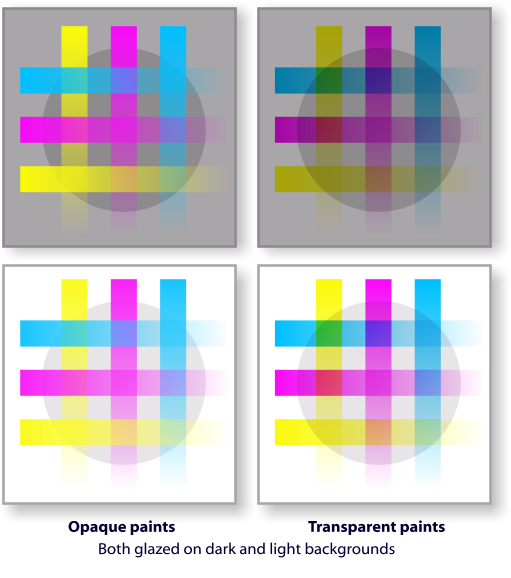

When I talk about my painting to others, I constantly see that the concepts of transparent vs. opaque paints are, ahem, "somewhat unclear" to most people. This is a brief attempt to clarify these concepts as they pertain to painting. And, since a picture is sometimes worth a gazillion dreary words, we'll start with this one:

That should be pretty self-evident, huh? No? OK, let me quickly elaborate a little.

Opaque paints

Transparent paints

Colors vs. colorants

It's important to note that any color — red, blue, green, yellow — can exist in either an opaque or a transparent form. This is a matter of the physical nature of particular colorants, regardless of whether they are pigments (insoluble substances) or dyes (soluble). So no color is in itself opaque or transparent — but particular paints are, depending on what colorant they are made of. For instance, Cadmium Red is an inherently opaque paint, whereas Alizarin Crimson is inherently transparent. But this is not a totally binary matter — there are degrees here — so calling a paint "opaque" or "transparent" is just an overall ballpark characterization. And even very opaque paints can be used at least semi-transparently, by glazing them.

Are your eyes glazed over?

In painting, to "glaze" is to use a paint in a more-or-less transparent manner, usually (though not necessarily) by diluting it with a painting medium: linseed oil, poppy oil, Liquin, Wingel — or countless others. Now, it's very common to speak of glazing only in connection with transparent paints, as if "glaze" and "transparent" were synonyms. But opaque paints can be glazed just as well — the graphic above clearly demonstrates this, and while that is a computer-created image (done in Xara Xtreme) things are no different in the world of physical paints. All it takes is to dilute the paint with a painting medium.