Out there

Friends

Commentary

Web design

Graphics

Computers

Painting

Photography

Klaus Nordby's militantly dull homepage

www.klausnordby.com/ego/bg-oct31.html

06-Apr-07

23:48

Bouguereau painting forgery blog

October 31, 2006: A Rose by any other colorant . . .

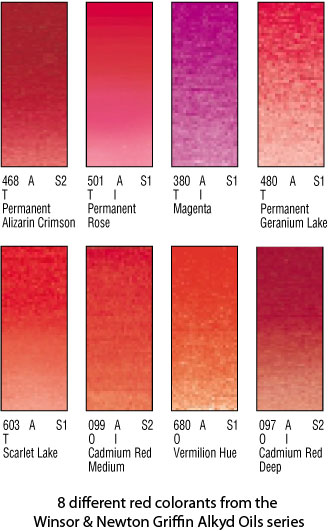

Every painting is executed using a certain palette — the particular colorants, the "tubes of

colors," the painter chooses to use. Obviously, if there is, say, a red rose in a painting, some red paint must be used for

that part of the painting — but which one: Cadmium Red, Alizarin Crimson, Scarlet Lake, Vermillion? These colorants are all "red"

—  but they are radically different in both hue, saturation and

transparency & opacity. So the appearance of the final rose is greatly affected by which colorant you choose for

painting it. Also, using only one red colorant for a rose would make it somewhat dull in appearance, so at least two reds should

be used — or more. Another approach is to use only one red colorant and modify it with other colors, like yellows, oranges and blues. And

then you'd have to choose which particular colorants to use for yellow, orange and blue — thus adding to your palette .

but they are radically different in both hue, saturation and

transparency & opacity. So the appearance of the final rose is greatly affected by which colorant you choose for

painting it. Also, using only one red colorant for a rose would make it somewhat dull in appearance, so at least two reds should

be used — or more. Another approach is to use only one red colorant and modify it with other colors, like yellows, oranges and blues. And

then you'd have to choose which particular colorants to use for yellow, orange and blue — thus adding to your palette .

The practice of mixing all colors from a few fixed primary colors, as is done in 4-color printing or on 6-7-8-color inkjet printers, would usually be a Bad Idea for painting: it would severally limit your possible color range (though there might of course be special cases where that is desirable).

The Iron Rule: As many as you really need — but no more

There can never be an iron-clad rule about "how many different colorants one should use" — for, depending on the painting's subject matter and color scheme, it might be three or thirteen. But, as a general principle, one can say "the fewer you need, the better" — because the more different colorants you use, the harder it becomes to make the painting chromatically integrated. Art is hard enough as it is, so whatever can make the poor painter's life a little easier is a Very Good Thing. I therefore always use as few colorants as possible.

A palatable palette, s'il vous plaît?

This Bouguereau copy will need 7-8 colorants, but I don't know for sure yet. I am now in the final stages of deciding on the exact palette for my Bouguereau copy — and will soon post the palette on my project blog.

But since my Bouguereau copy is just that — a copy — it might perhaps seem like a good idea to find out the exact palette Bouguereau himself used for this painting and use those colorants myself, thus sparing me the trouble of making my own palette? However, that's practically impossible, partly because there are no known records of which colorants Bouguereau used on this particular painting (though we have a complete list of all colorants he was known to use) — and because some of those colorants are no longer available. And that is largely a good thing, because in the 100 years which have passed since he Bouguereau died the science of paint chemistry has made major improvements to our possible palettes. The Winsor & Newton Griffin Alkyd Oils I am using are much better paints than what they had in the "good, old days": they dry faster and at a more even rate, they are virtually non-yellowing, they are not prone to cracking , they have a high degreee of transparency and the colors are purer and with better lightfastness.

A little rant

But a lot of traditionalists in the field of painting like to wail that we have "lost so much knowledge" about how the Old Masters used to paint and that so many great colorants and mediums which they had access to are now defunct, etc. — thus making it impossible to paint like they did. That is largely total nonsense. We have a staggering amount of knowledge about how they painted and what colorants and mediums they used — and almost all modern substitutes are vastly better regarding longevity, purity of hue and other technical matters. The reason why so few painters in our sorry age can "paint like the Old Masters" did has nothing to do with nitty-gritty paint-technical matters — and everything to do with how the "modern art" movement in the past hundred years have killed the art of painting philosophically, esthetically and educationally.